Dylan on the big screen

Hi All,

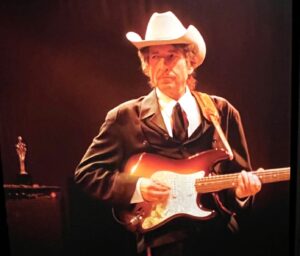

It’s almost Christmas and here’s a present for those of you, who like me, are Bob Dylan fans. The new biopic, A Complete Unknown, opens in cinemas on January 23 — it opens in the US on Christmas Day. I’ll certainly be getting a ticket as soon as the big day is over.

The movie’s name comes from a line in Dylan’s best-known song, Like a Rolling Stone. The film stars Timothee Chalamet as Dylan; Monica Barbaro as Joan Baez; Elle Fanning as Sylie Rosso (a fictionalised version of Dylan’s early girlfriend Suze Rotolo); Boyd Holbrook as Johnny Cash; Edward Norton as folk singer Pete Seeger, Eli Brown as guitarist Mike Bloomfield; Scoot McNairya as Woody Guthrie and Big Bill Morganfield (who is the son of Muddy Waters) as Leadbelly. A stellar cast of well known names and new faces – at least for me.

The film, which traces Dylan’s early days from the time he arrived in New York City of Minnesota until around 1965, was written by James Mangold and Jay Cocks, and directed by Mangold, who previously directed films including Girl Interrupted and Walk the Line.

By all accounts, Dylan has approved the film.

As a Dylan devotee, I am looking forward to it. But today I’d like to share a travel article I wrote about the Bob Dylan Centre I had the privilege of visiting (in Tulsa Oklahoma, no less) in May this year. The story, below, was published in The Australian newspaper on August 10, 2024.

I hope you enjoy it and perhaps think about a visit to Tulsa, which is a surprisingly fascinating city. While Tulsa is home to the new Dylan centre, it also houses the adjacent Woody Guthrie Centre and the Church Studios (and museum) once owned by the late musician Leon Russell. Tulsa grew rich from the discovery of oil in 1905 and this wealth led to the building of many fine Art Deco skyscrapers. They’re not as big as New York’s, but impressive nonetheless.

Here’s the article.

My obsession with Bob Dylan goes back to 1969; one might say “down the foggy ruins of time”. So when I hear podcaster Laura Tenschert, host of Definitely Dylan, chatting with the keepers of the Bob Dylan Archive, a treasure trove of 100,000 items that have found a home at the Bob Dylan Centre in Tulsa, Oklahoma, I decide then and there to go. After all, as a Sydneysider, I’m “only 24 hours from Tulsa”.

Located in the city’s arts district, the museum shares a century-old former warehouse with the Woody Guthrie Centre, opened a decade earlier. A prolific singer-songwriter and pioneer of social change, Guthrie hailed from Okemah, an hour south by road. As every Dylan diehard knows, Guthrie was Dylan’s muse, and the two formed a strong friendship after Dylan travelled to a New Jersey hospital to visit his ailing mentor in 1961. The idea for these shrines to two of America’s most influential singer-songwriters arose when Tulsa philanthropist George Kaiser acquired the Guthrie archives in 2011. Five years later he bought the huge Dylan collection. An oil-and-gas billionaire, Kaiser hasn’t revealed what he paid for the assortment of rarely seen photos, unreleased recordings, song lyrics, notebooks and ephemera that Dylan amassed over six decades, although pundits speculate it to be about $US20m ($30m).

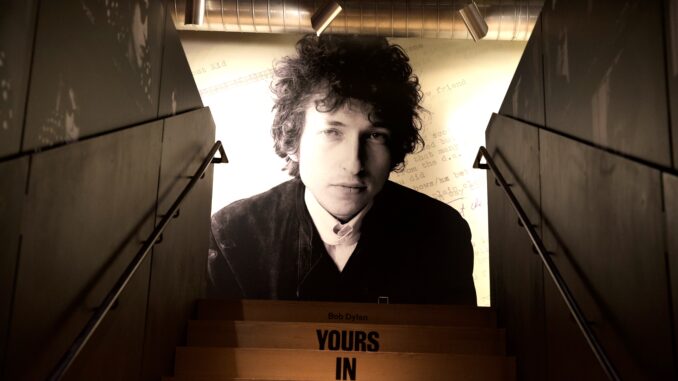

Standing across the road on Guthrie Green, another Kaiser-funded community project, I admire the 1965 Dylan portrait by photographer Jerry Schatzberg that graces the building’s exterior. On entry, a life-size photo of a young man in jeans and plaid shirt on the verge of stardom dominates one wall beside a 4.5m-high iron gate. Dylan, the ultimate Renaissance man, added metal sculpture to his repertoire about 30 years ago and donated the impressive piece.

I bypass the record and merchandise store (it’s dangerous to linger near so much vinyl) and enter a huge media room with a dozen screens suspended from the walls, an upright piano on a raised platform and sheets of music strung with wire as if their lyrics were flying off the keys in a restless flurry. The screens assail me with videos spanning 60 years – concert performances, press interviews, clips of reporters’ inane questions and Dylan’s bemused responses. There are home movies and scenes of the countryside as his tour bus rolls on. It’s a brilliant kaleidoscope of sound bites and celluloid with Dylan – as a young man, middle-aged and old – taking centre stage.

About 75,000 people from 40 countries have visited the BDC since it opened in May 2022 but I’m one of just 300 Australians to have made the journey. Director Steve Jenkins says most tourists don’t have the centre on their radar. They discover its existence once they arrive in Tulsa, a stop on the famed Route 66. The exception is Penn Jillette, one half of the American Penn & Teller comedy-magician duo, who holds the record for the most visits and who has spent hours poring over the collection. Dylan, Jenkins says, hasn’t visited and isn’t likely to. “He’s always looking ahead, he doesn’t look back.”

That said, the singer, 83, approved the location because of its Guthrie connection and its strong association with Native American people; with 39 tribal nations, Oklahoma has the country’s largest Native population. Displays in the main exhibition room trace Dylan’s illustrious career in themes and milestones rather than strict chronological order. For example, a panel depicting the early years is titled “Dylan Reinvents Himself” and features images from his childhood, of his first high-school band and his metamorphosis from Robert Allen Zimmerman to Bob Dylan.

I move from theme to theme, placing a small handset over a digital reader to listen to songs, interviews and concerts, delivered through earphones in crystal-clear sound. One panel details Dylan’s 1965 Newport Folk Festival performance where he launched his new electric sound, infuriating the crowd. Next to it, behind a glass case, is the black leather jacket he wore as the audience howled and booed. I linger at the “Like a Rolling Stone” panel and learn about the arduous song-making process and read about renowned guitarist Mike Bloomfield who played on the iconic track.

“The Man in Me” takes me back to 1970 when I bought the New Morning album that features the song of the same name, a track that gained major airplay years later when it opened the Cohen Brothers 1998 cult film, The Big Lebowski. It was written by Dylan at age 29, when he shunned the limelight to hunker down in Woodstock and embrace family life. The “Blood on the Tracks” theme deals with the creation of what many fans consider his best album. Here, I find the so-called Blood Notebooks, the centre’s holy grail of three books of lyrics scribbled down and crossed out in Dylan’s spider-like script.

“Pressing On with Jesus” outlines Dylan’s early 1980s Christian phase, a period that also met with derision, while another called “Down the Highway” includes a self-deprecating quote from the man himself: “I’m an empty burned out wreck … in the bottomless pit of cultural oblivion.”

Later achievements are told through his 1998 Grammy Award for the album Time Out of Mind, his popular show Theme Time Radio Hour, and the Nobel Prize for Literature a decade later. The narrative arc is fabulous, as is the jukebox with 162 Dylan songs and covers chosen by Elvis Costello.

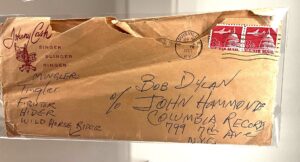

But I’m drawn to the little things: Christmas cards from George Harrison, get-well cards following his motorcycle accident, a letter from Johnny

Cash, his wallet containing Otis Redding’s business card and an address book with Lenny Bruce’s phone number. These “Bobjects” represent just 10 per cent of the archives but there is more than enough for casual observers and dedicated Dylanologists alike. The venue also stages concerts, screens documentaries and offers two annual song writing scholarships. Dylan might not look back, but I will definitely be returning.

For more information about Oklahoma and Tulsa, visit Oklahoma Tourism & & Recreation.

travelok.com

For information on the Bob Dylan Centre visit:

Photos: Provided by the Bob Dylan Centre and my own photos.

Be the first to comment