Travels of the exotic kind – following the Silk Route from Tashkent to Khiva

CRIMINALS and unfaithful wives were thrown from the Kalyan Minaret in Bukhara, known as the Tower of Death. I look up at this magnificent structure, 47 metres high, built in the city’s heyday of the 10th century. The practice of hurling people from the summit continued until 1884 when the Russians, who had invaded Uzbekistan a decade earlier, finally put a stop to it.

Two hundred kilometres away in Samarkand I listen as our guide tells us that human heads were impaled on spikes in the Registan – a huge square surrounded by three magnificent madrasahs – and the most stunning building in Central Asia. During my travels through Uzbekistan I hear many grim stories of macabre practices, but these are mixed with tales of noble heroes and kings, and I lap up every detail.

I visited Uzbekistan in May 1998 and scarcely saw a tourist, save for a group of Swiss who alighted from a tour bus one day. Our little party consisted of seven Australians, our fantastic 23-year-old guide, Radik, and our driver.

Recent internet photos paint a different picture; my searches show groups of tourists queuing to enter the most popular sites, while package tours that tend to combine Uzbekistan with a couple or all of the nearby ‘stans’ , such as Turkmenistan and Tajikistan, are on the rise. (Stan simply means ‘place’.) Below is part of my story, published in Vacations & Travel magazine in 1999. I feel very lucky to have travelled through this fascinating country, just seven years after it gained independence, when tourism was in its infancy.

Uzbekistan, May 1998: “After a 30-hour journey from Australia and an officious reception from immigration officers at Tashkent airport, it was a like a homecoming to be welcomed with tea and cakes into the home of two women, a teacher and her elderly mother, whose apartment became our hotel for the night. Our small group of seven Australians was split up for our first night in Uzbekistan; five stayed at the rather forlorn Hotel Tashkent, whose grandiose façade was very misleading, while my friend and I had inadvertently struck the jackpot when allocated to the modest home of these local ladies with whom we swapped nods, smiles and a few words of Russian.

The next day we were hitting the famous ‘Golden Road to Samarkand’, taking the much-travelled ancient journey to the legendary city of the Silk Route. Named after the most valuable commodity of the time, the Silk Route, dating from 138BC, was a system of roads that linked China to Imperial Rome. As the first country to breed silk worms and produce silk, China introduced the fabric far and wide during diplomatic missions over some two hundred years from the 2nd century BC. The Persians in turn were keen to trade it further afield and East literally met West as vast caravans crossed the deserts, laden with the precious cloth, together with spices, lacquerware, jade and arms.

Uzbekistan, the undisputed jewel of Central Asia, struck me as the very place where east and west had fused. Wedged between four former Soviet republics and bordered by Afghanistan to the south, tiny Uzbekistan has been invaded from all sides.

The big names of history passed through, creating and destroying empires in their wake. Alexander the Great conquered in the 4th century BC on his way to India; Turks invaded over the next three centuries until the Arabs brought Islam around 700AD. The Mongols came from the East in the 10th century culminating with the invasion of Genghis Khan who destroyed Samarkand and Bukhara but left the Kalyan Minaret untouched because, according to the history books, its sheer size ‘stopped him in his tracks’.

Around 1370 a Mongol chieftain called Tamerlane luckily decided to settle in Samarkand and embarked on a massive building plan, erecting the sensational monuments that survive today. He is Uzbekistan’s hero and his tomb is adorned with the most spectacular of the city’s many blue domes. The following 200 years were dominated by the Uzbek descendants of the Mongols, named after their ruler Khan Uzbek, while the Russians, who had been steadily advancing east in the 19th century, took over most of Central Asia in 1868.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Uzbekistan finally gained independence. The constant flow of caravans and the spread of Islam resulted in the construction of some of the most majestic buildings in the world, while the Soviets left their own legacy – tree-lined streets, brutal ‘Stalinesque’ architecture in Tashkent, vast cotton fields, the Cyrillic alphabet and cheap vodka. Our group was on a tour designed by Raisa & Associates, one of a handful of tour operators who had sprung up since independence. Mother of two and resident of Bukhara, Raisa worked for the Soviet travel agency Intourist for 20 years before starting her own business. Our guide Radik was of Tartar descent and our vehicle was a sturdy, but battered Soviet-built mini-van.

I wondered whether Samarkand could live up to the glorious images I’d seen in travel books. But as our van reached the city on a perfect May afternoon, the sight of numerous turquoise domes glistening with mosaics dispelled any of my doubts.

We were booked into a guesthouse, located just a five-minute walk from the Registan, owned by a charming man with the wonderful name of Furkat Rominov. The city’s masterpiece, Registan means ‘sandy place’ and legend has it that plenty of the substance was needed to soak up the blood of public executions.

We were scheduled to visit it in the late afternoon when the light would be perfect. Our first stop was Gur Emir – the tomb of Tamerlane. A huge labyrinth of ruined buildings including a mosque and a hanaka or hostel for wandering devishes, the actual tomb is topped with the most magnificent dome in the city, standing 32 metres high and fluted with 64 architectural ‘ribs’. It was actually intended as the resting place for Tamerlane’s grandson, but as Tamerlane died in battle in 1405 during its construction, the tomb was quickly finished and reassigned as the hero’s burial site.

Our afternoon visit to the Registan was brilliant, perfectly timed as the sun hit the millions of tiny mosaics that cover the facades of three madrasahs and the mosque. Certainly sensational today, the Registan would have been awe-inspiring in its medieval heyday when bustling with traders and camels and the hundreds of students who studied and lived in the madrasahs – the Islamic universities of the day.

We had the place to ourselves, save for one lone tourist also taking photos in the perfect light. The once-crowded madrasahs were empty save for a few traders, who had moved into the former cells and transformed them into shops where they displayed hand-woven carpets and artefacts. Business was slow and as our little group walked into one store, salesmen greeted us warmly and were more than happy to exchange our US dollars into local sums, at excellent black market rates.

The next day I took an early stroll to the Registan to catch the morning light and was surprised to see a man leading a small herd of goats out of a grim apartment block. He was obviously defying the local authorities who had banned citizens from keeping farm animals in apartment basements, but no doubt old habits die hard.”

There’s quite a bit more to my published story – but I think you get the gist.

Uzbekistan is the most splendid ‘place’. It houses more than 4000 archaeological and architectural monuments and it’s amazing to think that so many of these treasures were built in medieval times and have survived in relatively good condition despite the vandals and hooligans that overran Central Asia.

We visited just a handful of Samarkand’s treasures – the Bibi Khanym, the biggest mosque in Central Asia, built in 1399 and named for Tamelane’s Chinese wife and partially destroyed by several earthquakes, the last in 1897, and the Shan-I-Zinda, a series of tombs built from the 11th to 19th centuries.

Although the city has dozens of domes, minarets and dazzling mosaics, it was Samarkand’s people who turned out to be the surprise attraction. They were just as photogenic. At the market we saw women wearing dresses completely covered in sequins or tiny mirrors sewn into the fabric, worn over pantaloons made of rich gold-thread fabric. And we found unlikely items for sale. One member of our party who’d been to Uzbekistan two years earlier told us that freshwater pearls were an excellent buy. We tracked down the lady with the pearl stall and after six of us bought a few strings each, I bought the last batch of 11 strands for an the unbelievable price of A$4.50.

Bukhara, a UNESCO world heritage site, was our next stop reached after a five-hour journey across the desert. On the way we passed apple orchards and vineyards and just an hour out of Bukhara stopped to view the façade of the only remaining caravanserai in the country. In medieval times there was a caravanseri (accommodation for travellers and camels) every 40km, for that’s as far as a camel could walk without needing water. Now there’s only one left and it was crumbling. I’m not sure what condition it’s in today. While Samarkand is dazzling, I was equally taken by Bukhara and its many buildings, especially the complex of mosques and madrasahs that surrounds the Kalyan Tower, which includes the Miri-I-Arab Madrasah and an enormous square where 12,000 of the faithful worshipped.

One of my favourite buildings was the squat, four-towered mosque, Chor-Minor. It is quite new by Uzbekistan standards, dating from the 19th century. Each tower represents one of the religions of the day: Islam, Christianity, Buddhism and Zoroastrianism.

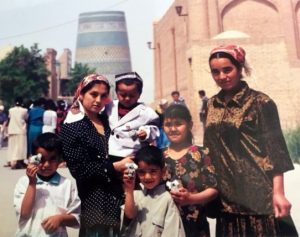

One of the reasons I’d love to return to Uzbekistan, is to spend more time in Khiva – the third main city. It struck me as a perfect film set where you could certainly stage a few Biblical movies. The old city is enclosed by two kilometres of mud-brick walls, protecting the ‘ark’ or fortress. Within the walls are several blue-striped minarets and towers and of course a range of mosques each topped with a dome.

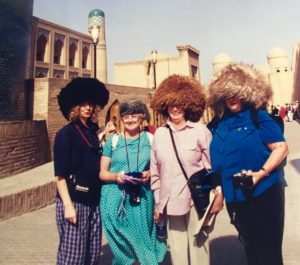

Here we mingled with traders and families, who were more than a little intrigued by seven Western women out of their own. We popped into a hat seller and tried on various styles of fur hat – in fact the merchant sold nothing but fur hats. It was fun trying on headgear that would not have been out of place on the set of Doctor Zhivago. I asked the merchant about a particular hat I liked – a fur pillbox – wanting to know its lineage, so to speak. His face erupted in a huge smile, displaying the gold-capped teeth that many folks, even the young men, seem to have. I expected something quite exotic but “water rat!” was what he proudly proclaimed. I didn’t hesitate after that and quickly struck up a bargain and he wrapped it up. (On finding my 20-year-old notebook recently I discovered the hat cost me US$15). I’ve never worn it – in Australia or anywhere for that matter; it was a spontaneous in-situ purchase – but I doubt I’ll ever part with it, nor the purple velvet coat I bought days earlier in Bukhara’s summer palace.

During our ramblings in Uzbekistan, I often struck out on my own to see what the shops held or to hunt down a bottle of wine. Once I returned with a bottle of red, which was more like port than table wine, and another time, picked up a bottle of vodka for $2. On another occasion we all went to a fabulous dance performance held in one of Bukhara’s old madrasahs.

The female dancers were dressed in robes made from a cloth called ikat, while the clothes of both men and women were stitched with silk thread in a style known as ‘suzani’ embroidery. I’d love to go back to Uzbekistan and spend more time wandering the markets and poking around the exquisite buildings, but I fear I will no longer have the place to myself. Rather than one lone tourist strolling through the Registan in the late afternoon, there’s bound to be hundreds and tour buses clogging the car park. Such is life on the road I guess – and especially the old Silk Road, now being rediscovered by a new band of wanderers.

Here’s a link to the company that arranged our tour 20 years ago. http://www.oxuscom.com/raisa1.htm

Here’s a link to another Uzbek travel and information site: https://uzbekistan.travel/en/

Be the first to comment